Screen shot of Amy Goldstein's talk at Politics and Prose.

Washington Post reporter Amy Goldstein is at Virginia Tech today as part of the Community Voices series, talking about Janesville (Simon and Schuster, 2017), her book on the evisceration of the working class in Wisconsin and the United States. Goldstein won a Pulitzer Prize in 2002 as part of the team that covered 9-11 and its aftermath.

I attended the lunchtime interactive roundtable discussion at GLC (Graduate Life Center) and I was struck by the contrast between her outsider approacher (she says an "oldtime" journalist there said it took an outsider to write this book) and the approach of her fellow Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard fellow, Beth Macy, who wrote a similar book in Factory Man (Hachette, 2014), as a journalist deeply imbedded in her community.

I think Goldstein and Macy share an approach towards interviewing, although I am struck that there are times that Beth has said that ethically she was willing to pass on a story. Also, Beth is willing to make her self a character in her books, whereas Goldstein maintains her journalistic distance, which Beth used only in her newspaper stories. Beth Macy tells me that in Factory Man's she cites (in the end notes] Goldstein's work on Pew Center survey about how the recession was only being covered top down—the fact that few bothered reporting from smaller communities harmed most by globalization and technology.

The person who introduced the speaker had an interesting comparison between Janesville and the auto industry and WV and the coal industry, in terms of some folk's reaction to the demise of a longtime employer.

I also attended a 2 - 3 pm interview with Goldstein. From 7-8, she gave an evening talk, "Reflections on Janesville: An American Story" in Squires.

Once they are read, there will be recordings of all three sessions here, thanks to Andy Morikawa.

2/19/18

Amy Goldstein: Janesville and the Evisceration of the Working Class

Posted by

Beth Wellington

at

8:54 PM

Amy Goldstein: Janesville and the Evisceration of the Working Class

2018-02-19T20:54:00-05:00

Beth Wellington

Amy Goldstein|Beth Macy|Janesville|recession|

Comments

Labels:

Amy Goldstein,

Beth Macy,

Janesville,

recession

2/17/18

Guest Post by Elizabeth Englander: Ten Ways Schools, Parents and Communities Can Prevent School Shootings Now

Photo by Miami photojournalist Wilfredo Lee for AP accompanied this piece of the same title published by The Conversation published 2/16/18 by Elizabeth Englander (profile, email) Professor of Psychology, and the Director of the Massachusetts Aggression Reduction Center at Bridgewater State University.

The Conversation is a collaboration between editors and academics to provide news analysis and commentary that is free to read and republish using a Creative Commons, no derivatives licence.

*

After a shooter killed 17 people at a Florida high school, many have expressed frustration at the political hand-wringing over gun control and calls for prayer.

As a parent, I understand the desire for practical responses to school shootings. I also absolutely believe the government should do more to prevent such incidents. But the gun control debate has proven so divisive and ineffective that I am weary of waiting for politicians to act.

I study the kind of aggressive childhood behavior that often predates school shootings. That research suggests what communities and families can start doing today to better protect children. Here are 10 actions we can all take while the federal government drags its heels.

What schools can do

Because educators observe students’ emotional and behavioral development daily, they are best positioned to detect troubled behaviors and intervene. In Los Angeles, for example, schools have successfully used outreach and training to identify potentially violent students before problems occur.

1. Teach social and emotional skills

Children learn social skills from everyday interactions with each other. Playtime teaches young people how to control their emotions, recognize others’ feelings and to negotiate. Neighborhood “kick the can” games, for example, require cooperation to have fun – all without adult supervision.

Today, frequent social media use and a decrease in free play time has reduced children’s opportunities to learn these basic social skills.

But social and emotional skills can – and should – be taught in school as a way to prevent student violence. Students with more fluent social skills connect better with others and may be more able to recognize troubled peers who need help.

2. Hire more counselors and school resource officers

Due to budget cuts, many schools have few or no trained school psychologists, social workers or adjustment counselors on staff. These mental health professionals are society’s first line of defense against troubled students – especially with the current increase in adolescent depression and anxiety.

In my opinion, school resource officers – trained police officers who work with children – are also helpful for students. While untrained officers may pose a threat to students, well-trained school resource officers can connect with kids who have few other relationships, acting as a support system. They are also on hand to respond quickly if crime or violence erupts.

Putting trained school resource officers and counselors in every school will cost money, but I believe it will save lives.

3. Use technology to identify troubled students

Technology may challenge kids’ social development, but it can also be harnessed for good. Anonymous reporting systems – perhaps text-message based – can make it easier for parents and students to alert law enforcement and school counselors to kids who seem disconnected or disturbed. That enables early intervention.

In Steamboat Springs, Colorado, one such tip appeared to prevent extreme violence in May 2017. Police took a young man who’d threatened to harm his peers into protective custody before he could act on his words.

Technology may challenge kids’ social development, but it can also be harnessed for good. Anonymous reporting systems – perhaps text-message based – can make it easier for parents and students to alert law enforcement and school counselors to kids who seem disconnected or disturbed. That enables early intervention.

In Steamboat Springs, Colorado, one such tip appeared to prevent extreme violence in May 2017. Police took a young man who’d threatened to harm his peers into protective custody before he could act on his words.

What communities can do

Communities also help raise children. With many eyes and ears, they can detect often smaller problems before young people grow into violence.

4. Doctors should conduct standard mental health screenings

Extreme violence is almost always preceded by certain behavioral problems. These typically include a propensity toward aggression, a marked lack of social connectedness, indications of serious mental illness and a fascination with violence and guns.

Doctors could detect these problems early on with a standardized screening at health checkups. If concerns arise, referrals to counseling or other mental health professionals might follow.

Doctors are an underutilized community resource. Regular check-ups could help prevent violence. Myfuture.com, CC BY-ND

5. Enlist social media companies in the effort to detect threats

Most young people today use social media to express their feelings and aspirations. In the case of school shooters, these posts are often violent. A single violent post is hardly a guarantee of homicidal acts, of course. But evidence strongly indicates that repeated expressions of this nature can be a sign of trouble.

I would like to see companies like Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat create algorithms that identify repeated online threats and automatically alert local law enforcement.

What parents can do

Parents and guardians are often the first to detect their child’s emotional struggles. Here are some tips for monitoring and promoting healthy emotional development at home.

6. Think critically about your child’s social media use

From virtual war games to cruel trolls, the internet is full of violence. The relationship between violent content and aggression hasn’t been consistent in research: Some studies see no relationship at all, while others find some correlation between violent video games and violent behavior.

This mixed evidence suggests that online content affects children differently, so parents must assess how well their child handles it. If your daughter likes “Assassin’s Creed” but is gentle, socially successful and happy, the onscreen violence may not be strongly impacting her.

But if your child is drawn to violent games and tends to be aggressive or troubled, discuss the situation with your pediatrician or school counselor.

7. Consider what your child is missing out on

Is your child sleeping properly? Do your kids socialize with other young people? These two behaviors are linked to mental health in children, and excessive screen time can reduce or diminish the quality of both.

Make sure digital devices aren’t disrupting your kids’ sleep, and schedule play dates if your kids don’t make plans on their own.

8. Assess your child’s relationships

Like adults, children need confidants to feel invested in and connected with their community. The trusted person can be parent, a family member or a friend – just make sure someone’s playing that role.

For children who struggle to make friends and build relationships, there are programs that can help them learn how.

Children need confidants to feel connected to their communities. AP Photo/ by Louisiana-based Gerald Herbert

9. Fret productively about screen time

Research shows that excessive screen time can damage kids’ brains. That’s alarming in part because parents can’t realistically keep kids entirely off devices.

So rather than just fret over screen time, focus instead on how children can benefit from a variety of activities. Evidence shows that children who experience different pursuits over the course of their day – from sports and music to an after-school job – are happier and healthier for it.

10. Talk with your child

This is both the easiest and hardest way to make sure your kids are doing OK. Children, especially teenagers, don’t always want to talk about how life is going. Ask anyway.

My research shows that simply asking children about their friends, their technology use and their day is an important way to show you care. Even if they don’t respond, your interest demonstrates that you’re there for them.

Try this one now. Ask your children what they’re thinking about the shooting in Florida and how they like their friends and school. Then listen.

Try this one now. Ask your children what they’re thinking about the shooting in Florida and how they like their friends and school. Then listen.

Children need confidants to feel connected to their communities. AP Photo/ by Louisiana-based Gerald Herbert

9. Fret productively about screen time

Research shows that excessive screen time can damage kids’ brains. That’s alarming in part because parents can’t realistically keep kids entirely off devices.

So rather than just fret over screen time, focus instead on how children can benefit from a variety of activities. Evidence shows that children who experience different pursuits over the course of their day – from sports and music to an after-school job – are happier and healthier for it.

10. Talk with your child

This is both the easiest and hardest way to make sure your kids are doing OK. Children, especially teenagers, don’t always want to talk about how life is going. Ask anyway.

My research shows that simply asking children about their friends, their technology use and their day is an important way to show you care. Even if they don’t respond, your interest demonstrates that you’re there for them.

Try this one now. Ask your children what they’re thinking about the shooting in Florida and how they like their friends and school. Then listen.

Try this one now. Ask your children what they’re thinking about the shooting in Florida and how they like their friends and school. Then listen.

Posted by

Beth Wellington

at

4:50 PM

Guest Post by Elizabeth Englander: Ten Ways Schools, Parents and Communities Can Prevent School Shootings Now

2018-02-17T16:50:00-05:00

Beth Wellington

childhood development|Children|Florida|gun control|mental health|parenting|school shootings|screen time|social media|

Comments

2/16/18

Guest Post by Brian DeLay: The American Public has Power Over the Gun Business – Why Doesn't It Use It?

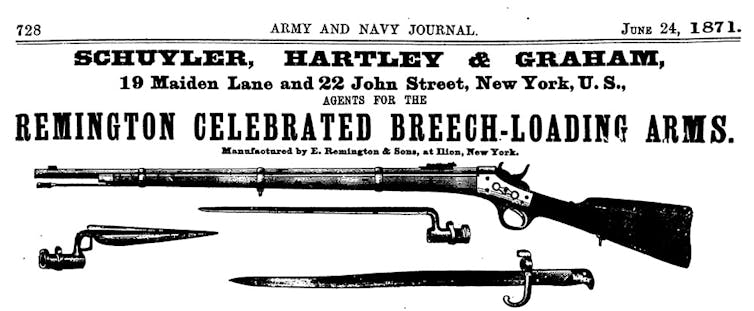

Photo by Miami photojournalist Wilfredo Lee for AP accompanied this piece by Brian DeLay published by The Conversation published an updated version of an article, "How the US government created and coddled the gun industry," published by the Conversation on 10/9/2017. The photographs in the body are also from the piece.

The Conversation is a collaboration between editors and academics to provide news analysis and commentary that is free to read and republish using a Creative Commons, no derivatives licence. DeLay, Associate Professor in History at the University of California, Berkeley (bio and contact information) is the author of War of a Thousand Deserts: Indian Raids and the U.S.-Mexican War (Yale, 2008), and is now at work on a book for W. W. Norton about guns, freedom, and domination in the Americas, called Shoot the State. Brian DeLay receives funding from the American Council of Learned Societies and the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation. University of California provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation.

*

On his facebook page, DeLay advocates even more specifically for how we might take on the NRA:

People who are sick and shamed by the way things are should take inspiration from the NRA and try to mobilize public consumers. Government contracts account for something like 40% of gun-maker revenue in this country. While citizen activism isn’t likely to influence military contracting anytime soon, states, counties, and municipalities buy lots of guns, too.

Again, take Smith & Wesson, maker of the AR-15 used to kill 14 kids and 3 teachers on Wednesday. S&W won the main handgun contract for the LAPD a few years ago. Most of Los Angeles’s leaders and their constituents support common-sense gun legislation, legislation that Smith & Wesson pays to prevent. And yet it doesn’t seem that Smith & Wesson’s political interventions hurt their ability to win the LAPD contract. In effect, gunmakers have learned to be highly sensitive to the NRA, but have not yet been made to worry that doing so will imperil the government contracting side of their business.

Why not make them worry? Ask your local, county, and state representatives where they get their guns. Gunmakers don't all kiss the NRA ring in the same way, but they're all locked in intense competition with one another. Big contracts matter. Even smaller public contracts matter, if for no other reason than the prestige of being able to say "X number of police departments across the country use our handguns." If enough concerned citizens make enough noise, our representatives might consider taking a firm's political activities into account when awarding contracts.

If a firm like Smith & Wesson lost even one major contract because its political activities imperiled public safety, that could be a powerful precedent and a check on their seemingly unrestrained embrace of the NRA and NSSF. It could be a start.

*

As teenagers in Parkland, Florida, dressed for the funerals of their friends – the latest victims of a mass shooting in the U.S. – weary outrage poured forth on social media and in op-eds across the country. Once again, survivors, victims’ families and critics of U.S. gun laws demanded action to address the never-ending cycle of mass shootings and routine violence ravaging American neighborhoods.

The 14 children and three adults shot dead on Feb. 14 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School were casualties of the nation’s 30th mass shooting this year – defined by the Gun Violence Archive as involving at least four victims including the injured – and one of the deadliest in U.S. history. A question on many minds is whether this massacre will finally compel Washington to act. Few commentators seem to believe so.

If advocates for reform despair, I can understand. The politics seem intractable. It’s easy to feel powerless.

But what I’ve learned from a decade of studying the history of the arms trade has convinced me that the American public has more power over the gun business than most people realize. Taxpayers have always been the arms industry’s indispensable patrons.

Washington’s patronage

The U.S. arms industry’s close alliance with the government is as old as the country itself, beginning with the American Revolution.

Forced to rely on foreign weapons during the war, President George Washington wanted to ensure that the new republic had its own arms industry. Inspired by European practice, he and his successors built public arsenals for the production of firearms in Springfield and Harper’s Ferry. They also began doling out lucrative arms contracts to private manufacturers such as Simeon North, the first official U.S. pistol maker, and Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin.

The government provided crucial startup funds, steady contracts, tariffs against foreign manufactures, robust patent laws, and patterns, tools and know-how from federal arsenals.

The War of 1812, perpetual conflicts with Native Americans and the U.S.-Mexican War all fed the industry’s growth. By the early 1850s, the United States was emerging as a world-class arms producer. Now-iconic American companies like those started by Eliphalet Remington and Samuel Colt began to acquire international reputations. Even the mighty gun-making center of Great Britain started emulating the American system of interchangeable parts and mechanized production.

Profit in war and peace

The Civil War supercharged America’s burgeoning gun industry.

The Union poured huge sums of money into arms procurement, which manufacturers then invested in new capacity and infrastructure. By 1865, for example, Remington had made nearly US$3 million producing firearms for the Union. The Confederacy, with its weak industrial base, had to import the vast majority of its weapons.

The war’s end meant a collapse in demand and bankruptcy for several gun makers. Those that prospered afterward, such as Colt, Remington and Winchester, did so by securing contracts from foreign governments and hitching their domestic marketing to the brutal romance of the American West.

While peace deprived gun makers of government money for a time, it delivered a windfall to well-capitalized dealers. That’s because within five years of Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, the War Department had decommissioned most of its guns and auctioned off some 1,340,000 to private arms dealers, such as Schuyler, Hartley and Graham. The Western Hemisphere’s largest private arms dealer at the time, the company scooped up warehouses full of cut-rate army muskets and rifles and made fortunes reselling them at home and abroad.

More wars, more guns

By the late 19th century, America’s increasingly aggressive role in the world insured steady business for the country’s gun makers.

The Spanish American War brought a new wave of contracts, as did both World Wars, Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq and the dozens of smaller conflicts that the U.S. waged around the globe in the 20th and early 21st century. As the U.S. built up the world’s most powerful military and established bases across the globe, the size of the contracts soared.

Consider Sig Sauer, the New Hampshire arms producer that made the MCX rifle used in the Orlando Pulse nightclub massacre. In addition to arming nearly a third of the country’s law enforcement, it recently won the coveted contract for the Army’s new standard pistol, ultimately worth $350 million to $580 million.

Colt might best illustrate the importance of public money for prominent civilian arms manufacturers. Maker of scores of iconic guns for the civilian market, including the AR-15 carbine used in the 1996 massacre that prompted Australia to enact its famously sweeping gun restrictions, Colt has also relied heavily on government contracts since the 19th century. The Vietnam War initiated a long era of making M16s for the military, and the company continued to land contracts as American war-making shifted from Southeast Asia to the Middle East. But Colt’s reliance on government was so great that it filed for bankruptcy in 2015, in part because it had lost the military contract for the M4 rifle two years earlier.

Overall, gun makers relied on government contracts for about 40 percent of their revenues in 2012.

Competition for contracts spurred manufacturers to make lethal innovations, such as handguns with magazines that hold 12 or 15 rounds rather than seven. Absent regulation, these innovations show up in gun enthusiast periodicals, sporting goods stores and emergency rooms.

NRA helped industry avoid regulation

So how has the industry managed to avoid more significant regulation, especially given the public anger and calls for legislation that follow horrific massacres like the one in Las Vegas?

Given their historic dependence on U.S. taxpayers, one might think that small arms makers would have been compelled to make meaningful concessions in such moments. But that seldom happens, thanks in large part to the National Rifle Association, a complicated yet invaluable industry partner.

Prior to the 1930s, meaningful firearms regulations came from state and local governments. There was little significant federal regulation until 1934, when Congress – spurred by the bloody “Tommy gun era” – debated the National Firearms Act.

The NRA, founded in 1871 as an organization focused on hunting and marksmanship, rallied its members to defeat the most important component of that bill: a tax meant to make it far more difficult to purchase handguns. Again in 1968, the NRA ensured Lyndon Johnson’s Gun Control Act wouldn’t include licensing and registration requirements.

In 1989, it helped delay and water down the Brady Act, which mandated background checks for arms purchased from federally licensed dealers. In 1996 the NRA engineered a virtual ban on federal funding for research into gun violence. In 2000, the group led a successful boycott of a gun maker that cooperated with the Clinton administration on gun safety measures. And it scored another big victory in 2005, by limiting the industry’s liability to gun-related lawsuits.

Most recently, the gun lobby has succeeded by promoting an ingenious illusion. It has framed government as the enemy of the gun business rather than its indispensable historic patron, convincing millions of American consumers that the state may at any moment stop them from buying guns or even try to confiscate them.

This helps explain why the share price of gun makers so often jumps after mass shootings. Investors know they have little to fear from new regulation and expect sales to rise anyway.

A question worth asking

So with the help of the NRA’s magic, major arms manufacturers have for decades thwarted regulations that majorities of Americans support.

Yet almost never does this political activity seem to jeopardize access to lucrative government contracts.

Americans interested in reform might reflect on that fact. They might start asking their representatives where they get their guns. It isn’t just the military and scores of federal agencies. States, counties and local governments buy plenty of guns, too.

Take Smith & Wesson, maker of the AR-15 Nikolas Cruz just used to kill his teachers and classmates at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Smith & Wesson is well into a five-year contract to supply handguns to the Los Angeles Police Department, the second-largest in the country. In 2016 the company contributed $500,000 (more than any other firm) to a get-out-the-vote operation designed to defeat candidates who favor tougher gun laws.

Do voters in LA – or in the rest of the country – know that they are indirectly subsidizing the gun lobby’s campaign against regulation? Concerned citizens should begin acting like the consumers they are and holding gun makers to account for political activities that imperil public safety.

Posted by

Beth Wellington

at

5:10 PM

Guest Post by Brian DeLay: The American Public has Power Over the Gun Business – Why Doesn't It Use It?

2018-02-16T17:10:00-05:00

Beth Wellington

assault rifles|Florida|gun control|gun deaths|gun industry|gun laws|gun policy|gun reform|guns|handguns|Las Vegas shooting|mass shootings|NRA|

Comments

2/8/18

The Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma: Coal Colonization and Opioid Addiction

That's West Virginia native Wayne Coombs writing in "Analysis: the Pharmaceutical Colinization of Appalachia, was published by Daily Yonder on 2/7/18 and forwarded by Roy Silver, professor of sociology on the Cumberland campus of Southeast Kentucky Community and Technical College since 1989.

In his article, Coombs, references a story he heard years ago, that had great resonance for his work in treating addicts:

One afternoon, a group of townspeople sees a baby in the river. One person dives in and rescues the infant. But as he climbs ashore, one of the other townspeople spots another baby in the river in need of help. Then another. And another. Overwhelmed by the sheer number of babies, the townspeople grab any passer-by they can to help them.

Before long, the river is filled with desperate babies, and more and more rescuers are required to assist the towns people. Unfortunately, not all the babies can be saved. And, tragically, some of the brave rescuers occasionally drown. But they manage to mold themselves into an efficient life-saving organization and, over time, an entire infrastructure develops to support their efforts: hospitals, schools, foster care, social services, trauma and victim support services, lifesaving trainers, swimming schools, etc.

At this point one of the town citizens starts walking upstream.

“Where are you going?” the others ask, disconcerted, “We need you here! Look how busy we are trying to save these babies!”The citizen replies: “You carry on here. I’m going upstream to find the bugger who keeps chucking all these babies in the river.”

When seeking an answer for why communities in Central Appalachia are so vulnerable to addiction, he found the conclusions of the ARC report Appalachian Diseases of Dispair by Michael Meit, Megan Heffernan, Erin Tanenbaum, and Topher Hoffmann of the The Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at the University of Chicago "upside down."

Are they saying that poverty causes this vulnerability? It seems much more likely that these problems, just like the diseases of despair, are symptoms and outcomes rather than its causes. What is it that creates this vulnerability? Obviously, something deeper is happening here.Coombs notes that that higher rate of death doesn't correlate with economic conditions and links to another article in Daily Yonder that in turn cites "Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century (2017),” in which Princeton Professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton rebut the prevailing argument that economic decline causes opioid crisis. (This follows up on their 2015 study, "Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century.")

In looking at maps of West Virginia, Coombs realized that the counties with the greatest substance abuse problems also had coal mining. He couldn't buy that the solution was to blame the victim.

I was aware that folks who were struggling with addictions most often came from families and communities who were also struggling with addictions, but this was usually accounted for through family dynamics. In other words, dysfunctional families begat dysfunctional kids who became dysfunctional adults who begat more dysfunction. However, the explanation did not really explain anything other than it was a problem of the people themselves and that is usually where the explanation ended. There was nothing about how the dysfunction got there in the first place or what kept it going. The only thing this explanation was good for was more subtly and “scientifically” blaming the people for their problems. But that explanation is bogus. What was happening here was different.Then he came across the Holocaust research of Rachel Lev Wiesel, "Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma across Three Generations (2007)."

Unfortunately, Coombs's conclusion offers no solution, only a question:

How can Appalachian communities – and others affected by historic trauma – heal from these wounds and go about the business of creating the kind of communities they really want? Answer this question, and we will go a long way toward solving the problem of addiction.Beth Macy has a new book coming out in August, Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America. According to her recent talk at the Radford library, she looks at not only those addicted to opioids, but at those currently trying to help them heal. I'm wondering if any of these healers are addressing the larger issue of historic trauma and overall community change. Beth certainly knows the history of trauma, as revealed in her review of Ramp Hollow, but it won't be simple, as she wrote:

Four years ago, I spent a few days reporting from the poorest county in West Virginia, one of the poorest states in the nation. The mayor of War (pop. 800, give or take) had been killed by an in-law’s brother in a drug-fueled rage months before. At the time, the mayor had been working in earnest to clean the town’s water, improve access to drug treatment and attract new industry, but as one unemployed young woman told me: “Not enough people here can pass a drug test.”

Posted by

Beth Wellington

at

4:14 PM

The Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma: Coal Colonization and Opioid Addiction

2018-02-08T16:14:00-05:00

Beth Wellington

Beth Macy|coal mining|colonization|intergenerational trauma|opioids|

Comments

Labels:

Beth Macy,

coal mining,

colonization,

intergenerational trauma,

opioids

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)